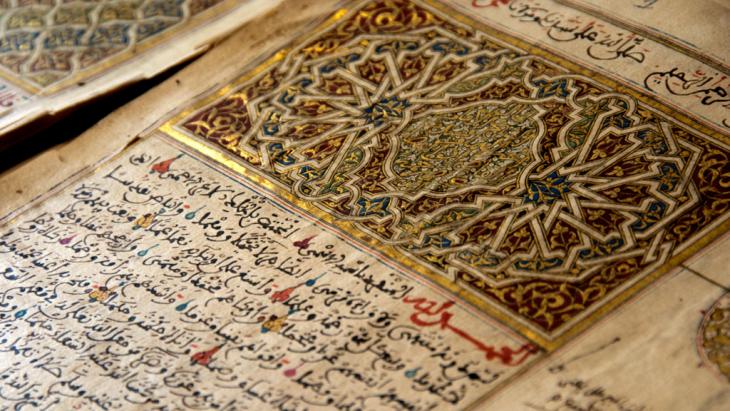

One evening during my graduate studies I was sitting in my apartment perusing through a short compilation of the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings (known in Arabic as hadith). Being always curious about religion, my roommate inquired me what I was up to. Upon hearing my response, she remarked that she had heard the most authentic hadith compilations in Islam were written down a couple of hundred years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad; and if that indeed was the case, how could I take what I was reading seriously and pretend that those were actually the words of Muhammad verbatim? I recalled that I had recently sat through a class on East Asian Religious Traditions wherein the Professor mentioned that the Buddhist texts were formally compiled and written down many centuries after Buddha’s death, and they were initially passed on orally by the monks down the generations. And this detail was added in quite a non-controversial, matter-of-fact manner: a sign of the centrality of orality in ancient cultures rather than a reason to doubt the authenticity of the religious literature in question. The exchange that followed with my friend got me ruminating about our widely prevalent, deep-seated, almost-reflexive modern bias which makes us disregard oral transmission as a reliable mode of knowledge transmission and treat only that which is committed to paper as truly authentic. I realized how important it is for us to appreciate the pre-modern emphasis on orality before we find ourselves tempted to suspect the authenticity of an entire religious literature based on a lack of early written records. Here I explore the role of orality in the formation of Islamic scriptural and religious tradition.

The word hadith lexically means speech or communication but gradually it came to mean the reports from the Prophet Muhammad in particular: the words he said, the actions he did, and also the actions by others he quietly approved. Being in awe of him, his companions who rubbed elbows with him and his followers who saw him on occasion keenly observed his behavior and felt it crucial to commit to memory anything, special or mundane, that could be reported about him — for pietistic or legal purposes. These people began to transmit the hadiths. Technically, every hadith is composed of the main text (called matn) of the report and the chain of transmission (called isnad) i.e. the full names of the transmitters who relayed the text.

The Prophet Muhammad died in 632 CE and the first two centuries after his death saw an emergence of ad hoc pamphlets and sporadic written records of his sayings. Then a little later a few thematic or transmitter-based compilations of the Prophetic sayings mixed with quotes from his companions (who the Muslims also revere) also appeared. In the absence of any particular filters of verification at this stage, both reliable as well as highly unreliable hadiths made their way into these compilations. Since this was a politically tumultuous time, a plethora of evidently forged hadiths began to emerge to support certain sectarian biases. Fabricated hadiths appeared for a whole host of other apolitical reasons too such as purely personal motivations. For example, an onion seller could stand to benefit from disseminating a fabrication attributing it to the Prophet Muhammad that whoever eats onions abundantly will have his/her sins forgiven and will be sent to heaven! At other times, an unintentional negligence or forgetfulness led people to confuse someone else’s saying with a hadith. This creeping of blatant forgeries or unwitting errors into the already amorphous body of hadiths began to trouble the concerned of the time. The upside of these pervasive fabrications was that some Muslim scholars got alarmed by the situation and intended to remedy it — before it gets further out of hand — by developing highly rigorous criteria for investigating the reliability of hadith. This led to a movement of authentication, most significant in the development of hadith literature, which produced the corpus considered the most accurate today. This stage was marked by meticulous standards and processes of authentication including investigation of each narration to sift the reliable from the unreliable. Reportedly this period also witnessed extensive travelling by the compilers to collect any bit of data needed for their investigation. All this flurry of scholarly activity eventually resulted in the compilation of six comprehensive canonical hadith collections.

While developing this collections, hadiths began to be classified and placed on a spectrum of authenticity. The four grades assigned to hadiths were sahih (sound/authentic), hasan (good), da’if (weak), and mawdu (fabricated). Sahih was the highest level of authenticity that was declared after the hadith was examined from multiple perspectives and passed various criteria: for instance the chain of transmission of the report was unbroken; the narrators were widely recognized as truthful and trustworthy; the report contained no outlandish content; it was consistent with the Quran, prophetic language, and the tests of historical evidence and so forth. Hasan grade was assigned to the hadiths that fell slightly short of the accuracy standards and fell in the second tier of reliability. The narrators of these reports were considered not to be completely unreliable but some doubt would persist concerning the retentiveness of their memory and accuracy of their reports. Ahadith would be classified as da’if if it failed to meet the requirements of the sahih and hasan classifications e.g. if its chain included one or more persons of highly questionable reliability. Finally, a mawdu hadith was the one known to be outright forged because it simply failed all criteria of establishing authenticity.

Since, the whole business of classifying hadithsdepended heavily, if not completely, on classifying people as good or bad transmitters, highly developed disciplines were formulated solely to examine the reliability of narrators e.g. ‘ilm al-rijal (the study of people) which dealt with the classification of narrators according to their levels of reliability and trustworthiness; and jarh wa al-ta’dil (impugning and validation) which did researched on personality evaluations bringing together grounds upon which narrators could potentially be disqualified or rendered unreliable — for instance, if a person had a reputation for lying, negligence, embellishment and fabrication, impious behavior or an absence of God-consciousness, obscurity or lack of personal identification, sectarian biases, or active involvement in political disputes etc. Based on these evaluations, reference books were compiled classifying transmitters according to their scores of trustworthiness.

Despite all the hard work that went into these processes of authentication, the scholars of hadith were realistic enough to admit that while sahih was the highest grade they could assign a hadith, a sahih status does not guarantee an absolute 100% reliability: even though highly sound, a sahih hadith was still considered probabilistic albeit with a very high possibility of reliability. The converse was true for the da’if hadiths in that while they were viewed as highly weak, they would not be outright rejected or considered totally unreliable with absolute certainty (unlike the mawdu hadiths which might get that treatment.) While the margin of error of a da’if hadith was significantly greater than that of sahih or hasan hadiths, it could not have been proven for sure to not have been said by the Prophet, most scholars agreed. So Muslim scholars by and large agreed to retain using weak hadiths for the innocuous ends of ‘encouraging virtuous actions’ but they would not be used for more serious purposes such as making law or establishing theological beliefs. While there is still a margin of error to sahih, hasan, and da’if hadiths, there is one category, containing merely a handful of hadiths, known as the mutawatir (ubiquitous or continuously recurrent) hadiths which the scholars unanimously agree to be absolutely reliable based on their frequency of narrations more than any other criterion. These were the narrations reported by such a large number of people in every generation which made them almost axiomatic hence precluding the possibility that they could be fabricated.

The two scholars who spearheaded the authentication movement and put together the most authentic hadith tomes were known as al-Bukhari (d. 870) and al-Muslim (d. 875). Comparing the years during which the Prophet Muhammad lived with the time when al-Bukhari and al-Muslim assembled their works, many might be tempted to conclude that the large time lapse must mean that hadiths are probably entirely fictitious since they had no way of being accurately preserved over all the years if they were not put down in black and white. In short, many aspersions on the integrity of a literature can be cast based simply on the fact that it was supposedly written down so late. This skeptical approach tends to ignore two important historical aspects. Firstly, during the entire two and half centuries that transpired between the Prophet’s death and the canonization of his speech, a lot of rudimentary work continued to be done to gather and preserve hadiths — and only because the hadiths were ultimately canonized and collated 250 years later, all this intermediary work through the previous years tends to get ignored. Secondly, viewing a formal systematized written record of something as the ultimate guarantor of its validity completely overlooks the role of orality in pre-modern civilizations in which oral discourses were predominant and reports and literatures would be carried down the generations through oral transmissions. In this context, it appears to be a modern, biased de-contextualization to insist that only that which has been committed to paper is true and credible knowledge. Our ancestors had different modes and standards for preserving and transmitting knowledge that must be evaluated on their own terms. Like many ancient peoples, historically the Arabs too — having a deep penchant for composing, reciting, and hearing poetry — generally had incredibly retentive memories so much so that it is said that many were able to recite tremendously long poems all by heart and considered it a disgrace, an unthinkable aberration, to have the need to preserve poetry in writing — much like the completely oral composition of poetry in the Greek Dark Ages. In ancient milieus such as the Athenian democracy, there was a reliance on oral communication rather than writing even in the domains of politics and law e.g. in establishing contracts, transactions, legal wills and witnesses etc. So a dependence on oral communication rather than the written word was a common pre-modern feature across cultures. Counterintuitive to modern sensibilities, a good memory was considered as a highly reliable tool to transmit knowledge across and down the generations. It is in this historical context that memorization as a mode of preservation of hadith in the first few centuries of Islam was not considered to be a lesser method. This also makes sense because reportedly no written tradition existed in Arabic before Islam in that there was no bureaucracy, no written archives, no court records, and most importantly there was no paper. Materials such as papyrus, parchment, wood, and bones were used for writing which were obviously in limited supply so they ought to be used scarcely and reports worth preserving were mostly committed to memory. Even while there are reports that some of the Prophet’s sayings were sporadically written here and there even during his lifetime (since some types of orality were not seen as mutually exclusive to some use of writing), generally things that were written down were not viewed as comprehensive records but merely as ad hoc aids to the memory. In the early hadith studies and circles, oral transmissions were considered to be superior to written ones: hearing (sama’a) a hadith from a teacher/narrator and relaying it orally was considered a more respectable practice than finding (wijada) a written report somewhere without audition and attempting to transmit it without authority. In contemporary language, the latter act could be conceived as equivalent to the modern academic offence of plagiarism that can significantly undermine ones credentials and respect in the eyes of their peers.

This importance of orality is also essential in our understanding of the primary scripture of Islam i.e. the Quran which the Muslims believe to be a revelation of God communicated to Prophet Muhammad which was subsequently memorized, transcribed, and preserved. The word Quran is derived from its trilateral root (q r ‘) lexically meaning something like ‘recitation’ and ‘reading’ arguably the meaning inclining more towards the idea of recitation. Reciting is seen as an activity distinct from reading in that the former can be done completely out of memory while the latter assumes that there is a written script from which the reading is done. When we think of Quran today, we imagine it in the form of a tangible book but it is important to know that historically before the Quran became a formally written scriptural reality, its oral dimensions were far more significant and it was viewed primarily as an oral communication. Its written records, which the Prophet had his scribes note down, were initially treated merely as an aid to the memory. During the 23 year period in which it gradually revealed, Prophet Muhammad and his companions experienced the Quran as a recitation and not as a cover-bound book as we encounter it today. After the Quran was organized and compiled following the Prophet’s death, it was the first ever book written in the Arabic language. Even while the Arabs were an ancient people, their central literary mode was oral poetry, as noted earlier; so naturally an oral Quran was more popular because of their high oral skills and their lack of reliance on writing.

Today we tend to associate scripture with written word because all religious traditions have come to have concrete scriptures, but the more we go back in history the more traditions we find where communities had a central word without having a written word — be it the Vedas of the Hindu Tradition or the Dhammapada of the Theravada Buddhist Tradition. The Quran was also predominantly oral in the beginning. Even while it was written down very early on, writing was not how it was taught or transmitted. This also explains why the ability to beautifully and mellifluously recite the Quran became a methodical and sought after skill. For the Muslims, Quran was the holiest of the holy words — the divine speech; and any mistakes could potentially desacralize or corrupt it. Written transmission was considered unwieldy and highly prone to scribal errors in the process of copying — so oral transmission was believed to a more practice, reliable, and intimate mode for learning and imparting the Quran. Again, this is reasonable in the aforesaid context wherein a deep reliance on memory retention is the natural upshot of an absence of a developed written tradition, resources, paper, or printing presses. There are still some places in the Muslim world where students learn and memorize the Quran by hearing it rather than interacting with its written form.

Those who are familiar with the early Arabic orthography would be quick to appreciate the centrality of an oral transmission of the Quran in its early stages. Quran was initially written in an early kufic script which is called ‘defective’ because of its highly inadequate nature in that it did not have diacritical marks or short vowels making it almost impossible to recognize the pronunciation of the word in case of a lack of prior familiarity with it. To give one small example: if one writes the word ‘elephant’ in Arabic without any diacritical marks or short vowels, there are many different permutations of how the word could be read; it could be read to mean ‘before,’ ‘it was said,’ ‘he murdered,’ ‘he was murdered’ and so on. Those who were orally familiar with the Quran having memorized it would know how to read a word as originally intended and could also transmit as such. When the fourth Muslim caliph sent the early Quranic manuscript to different regions that were coming under Muslim rule, he would also accompany an oral reciter with it to ensure the errors in pronunciation were minimized and the original meaning was preserved. Those who were encountering the text for the first time without the aid of an oral transmitter could not tell how to accurately read a word and this explains the eventual need to systematize and develop the script in a way that indicated the exact pronunciation. So, the early inadequate Arabic orthography demonstrates how crucial memorization must have been in the transmission of the Quran since the written text was less than enough to verify the extent of standardization that was eventually achieved.

In this historical context, relying on oral communication for the preservation and transmission of sacred knowledge was a norm rather than an aberration. This is true not only for the Quran and hadiths but also for another important genre of Muslim literature, sira i.e. the biography of the Prophet. The medieval sira literature was first crystalized between the late 8th through the early 10th centuries; so about 150 years transpired between Prophet Muhammad’s death and the formal emergence of sira as a genre of historical literature. Again, this substantial time lag could very well be an indictment of the authenticity of this literature, or it could also very well indicate that sira literature significantly drew onto memorized traditions and reports passed down the generations which the biographers then used to construct the narrative account of the Prophet’s life. These reports might or might not have been true. Ibn Ishaq (d. 768) who was the first to write formal sira biography of the widest scope got good deal of censure for his work. Some hadith scholars criticized his history-writing on the basis that his use of the chains of transmissions was inappropriate and his corroborations of events weak: that often he would not name the witness/narrator of a certain incident; attribute a certain report to a group of people rather than a single identifiable individual; use broken chains; or not mention the chain of transmitters for a report at all — all of this alleged laxity was not in line with the standards of the increasingly rigorous scholastic tradition of hadith but was tolerated within the conventions of sira. Many hadith scholars were shocked by Ibn Ishaq’s way of reporting and refused to deem his work worthy of too much credibility for their purposes. Yet, this work continued to remain influential even when some Muslims often also found certain incidents reported in the medieval sira to be controversial (much of which were redacted in the later development of sira literature). One historical view maintains that Muslim biographers and historians of that time were so meticulous about preserving history that they chose to report all the oral traditions they could gather — even it at times the report offended their own or the readers’ pious sensibilities, or even if the reports came without their proper citations of sources of information. They probably chose to let the generations of future scholars sort out the authentic from the inauthentic after the latter have access to all the written records at their disposal, rather than attempting to edit their data and lose historical material in the process. Ibn Ishaq reported in his book any oral traditions he could get his hands own, sometimes even two remarkably conflicting reports about the same event side by side (!) which is oddly different from the way we imagine a historical account in the modern context. So history writing in the context of orality appears to be a far cry from the modern demands of precision; and in a predominantly oral culture where history initially circulated in the form of oral reports, a reliance on orality to construct history does not seem like an anomaly.

While today we tend to treat written records as one of the most authentic forms of preservation of knowledge, it is good to keep in mind — particularly when looking at history of religion — that in pre-modern cultures writing was done much less frequently than modern people would like to assume. There was a time when oral transmission of literature and knowledge, of divine word, prophetic sayings, or historical events was considered to be perfectly acceptable and reasonable — perhaps even preferable — according to the standards of the time. It is wise to understand and appraise a culture — or a religion born out of that culture — according to its own terms, rather than viewing it through the lens of modern norms, treating it in isolation from its context, and undermining its complexity in the process.