“Are those who know equal to those who do not know?” (Q 39:9)

Being a graduate student of the study of Religion, every day is an eye-opener for me – a stark reality check – about how much there is to learn and how negligible a proportion of it I have managed to know so far. Clearly, a two-year long degree programme was not going to make me an expert on the intricate matters of faith and, most certainly, I will not pretend that it has. However, perhaps not everybody shares my degree of self-doubt. Recently, I heard one of my class-fellows voice his opinion in the class to this effect: “We need to take the legal tradition of Islam from the scholars who have monopolized it and give it to the ordinary people.” This got me to ruminate the entire day on how problematic I find this opinion to be. This article is precisely a cathartic outlet to that very rumination.

I would like to believe that the speaker’s opinion came from a well-meaning place, but I wonder who is this ‘we’ who’s bent upon snatching the tradition away from the scholars? Is it not an alarming case of intellectual hubris when individuals in their 20s, with barely two to three semesters of training in a religious studies degree based in a Western institution not only deem themselves fully qualified to take the Islamic tradition away from the scholars but also believe that scholarly contributions to the tradition can be bypassed in favor of individual efforts and interpretations. Presumably, the aim of this endeavor is the democratization of knowledge. It is needless to say that this is not a novel suggestion. The Protestant idea of everyone being entitled to access the scripture individually on their own and interpret it for themselves, and the modernist emphasis on breaking the chains of centuries worth of scholarly tradition in order to eradicate the intellectual stasis is echoed on the other end of the spectrum of modern madness when enraged accountants and engineers convince groups to go on killing sprees based on their ‘interpretations’ of the book. The increasing radicalization in the Muslim world in the past century is the very fruit of unqualified individuals interpreting scripture on their own, without the requisite tools, bending it to all sorts of devious and heinous ends.

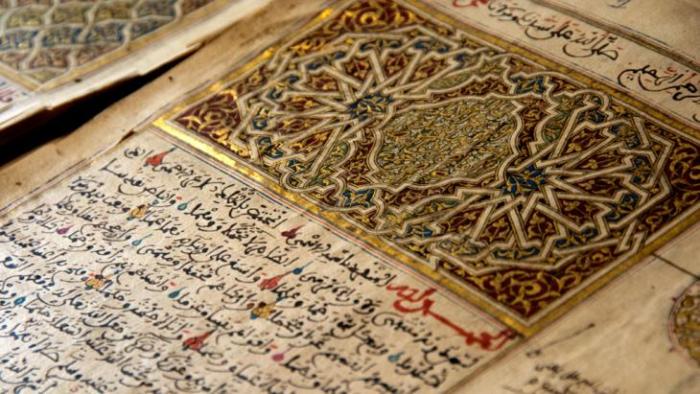

On the one hand, I wholeheartedly concede that that the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet is not a monopoly of the select few but a collective inheritance of the believers. On the other hand, I also firmly believe that that there has to be a systematic ethic with which this inheritance is to be viewed. Quran and hadith comprise not only of unequivocal general ethical exhortations but they also contain specific, legal, and deeply perplexing content, to comment on which scholars traditionally received training for decades within multiple religious sciences before they considered themselves qualified. And since everyone does not have the temperament, ability, or desire to possess these requisite tools, it is encouraged that when seeking clarity on crucial matters one asks those who do.

Certainly universal ethical principles can be consumed individually, but Quran and hadith are not entirely composed of ethical principles. How do ‘common people’ derive clear doctrinal precepts from scripture? Have they historically done so without utilizing the heritage of the scholars? Commenting on the verse 16:44 wherein the Prophet is reminded that Quran is sent down to him so that he may ‘explain it to the people,’ Taqi Usmani writes that “Had the interpretation of even this type of subjects (doctrinal issues) been open to everybody irrespective of the volume of his learning, the Holy Quran would not have entrusted the Holy Prophet with the functions of ‘teaching’ and ‘explaining’ the book.”

Even after the Prophet, Quran clearly encourages one to ask those who know and explicitly reminds that not everyone ‘knows’; undoubtedly, everyone is not at the same station of knowledge.

“Are those who know equal to those who do not know?” (Q 39:9)

“Question the people of the Remembrance, if it should be that you do not know..” (Q 16:43)

“And these similitudes We mention before the people. And nobody understands them except the learned.” (Q 29:43)

“Rather, the Qur’an is distinct verses [preserved] within the breasts of those who have been given knowledge. ” (Q 29:44)

The classical intellectual heritage of Islam owes its existence to the works of committed scholars. In my modest opinion, a handful of self-styled modern religious ‘scholars’ who use and abuse religion for political ends must not lead one to discredit an entire tradition standing on the efforts, commitment, and wisdom of those authentic scholars – classical, post-formative, and present – the ‘heirs of the Prophet’ according to the famous hadith – who worked sincerely and relentlessly to preserve the integrity of this extremely rich and beautiful tradition.

Not only is Quran a difficult book, the hadith and sunnah are even harder: Ibn Wahb (d. 813), an Egyptian jurist who travelled to Medina to study with Malik ibn Anas, noted that he learnt so many hadiths that they began to confuse him, and if it weren’t for Malik through which God rescued him, he would have destroyed himself. Malik used to guide him to study some hadiths and leave some.

Islamic tradition has been and will remain, if any meaningful understanding of it has to be acquired, a tradition learnt under the guidance of teachers – under the shadows of the scholars. One of the modern sages who’s been my constant source of inspiration quoted these Arabic verses recently which I find most germane to this issue under discussion:

(at some point) the knowledge was transferred from the breasts to lines (of books) / but humans still remain keys to those books

And Allah knows best.